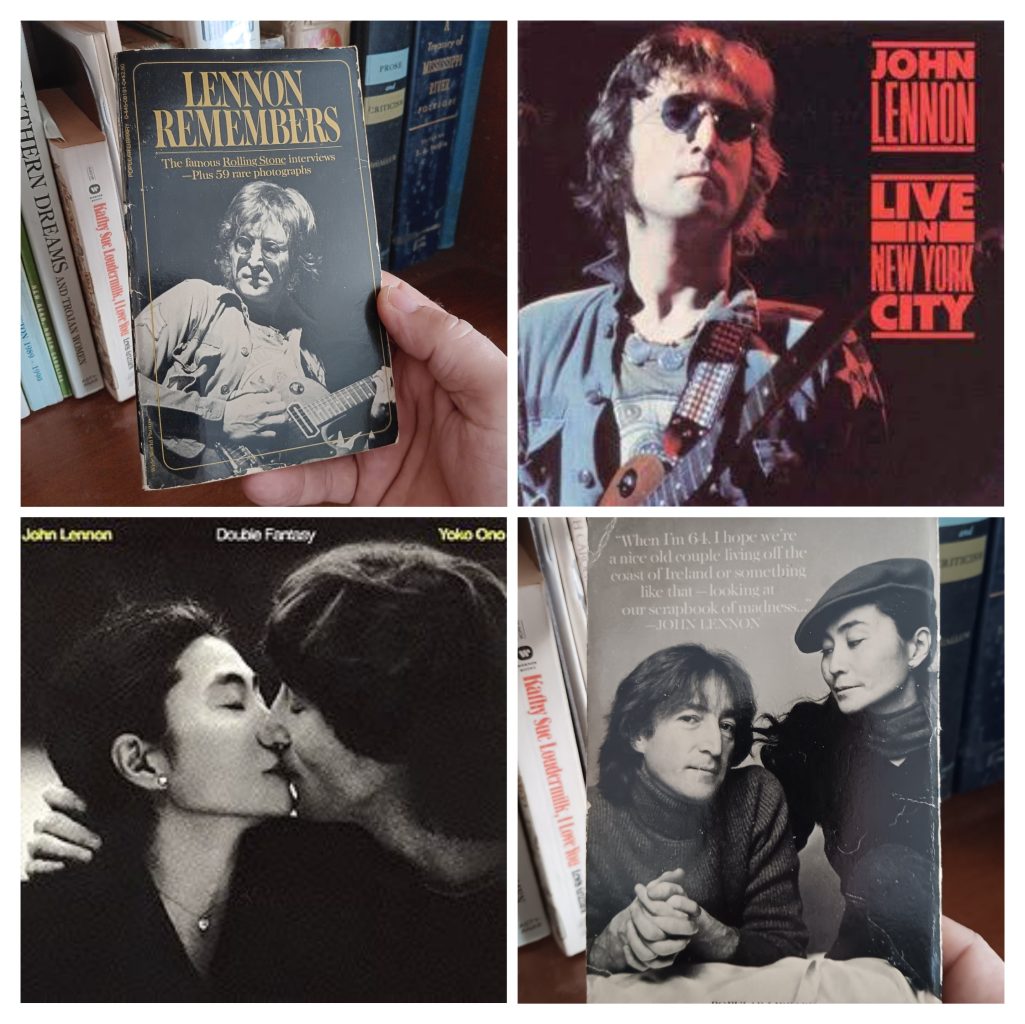

Fifty years ago John Lennon sang, “God is a concept by which we measure our pain.” I never fully understood that line until today when I read this psalm, despite the pain that I’ve endured.

Young David says, “[The enemy] has made me dwell in darkness, / Like those who have long been dead. / Therefore, my spirit is overwhelmed within me; / My heart within me is distressed.”

And still he prays, “I remember the days of old; / I meditate on all Your works; / I muse on the work of Your hands. / I spread out my hands to You; / My soul longs for You like a thirsty land.”

On our pedestals, we keep on playing those mind games long after we realize that “in [God’s] sight no one living is righteous.” But we can be working class heroes and dreamers. Imagine.