By RAHN ADAMS

MORGANTON, N.C. (Dec. 24, 2025) – No, I’m not going to criticize my wife Timberley here on Christmas Eve, not until after we open our presents, anyway.

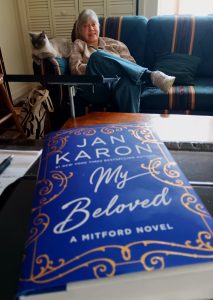

This is a brief review of Lenoir native Jan Karon’s latest Mitford novel, My Beloved, which I just finished reading aloud to Timberley as one of my gifts to her this holiday season. As I discovered in reading the heartwarming story, my gesture was like a common thread running through the book.

Actually, this is the second present my beloved wife and best friend has gotten early this year. The other one was The Chicken Encyclopedia for her to use with the children’s book she has started working on. Yeah, I know. I’m so romantic, huh?

But back to My Beloved. Over the past four decades, Ms. Karon, 88, has written 25 bestselling books, 15 of which are novels set in the fictional mountain village of Mitford. Her faithful readers—like Timberley—know that Mitford is really Blowing Rock, N.C., the Watauga County town where Ms. Karon lived for 10 years.

She moved to Virginia around the time that Timberley and I took teaching jobs at Watauga High School after our own 10-year sojourn, but on the N.C. coast. To my knowledge, our paths never crossed in Blowing Rock or Boone.

Or in Lenoir, where both Ms. Karon and I were products of the Caldwell County public school system—her, in and around the town of Hudson; me, at Happy Valley Elementary and Hibriten High. She credits her first-grade teacher, Nan Downs, with encouraging her love of reading and writing.

I must have been a late bloomer, because the educator who turned me on to reading and writing was Shannon Russing, my 11th-grade English teacher. I hope she knows how much I still appreciate the encouragement she gave me, a shy 16-year-old struggling to find my place among more privileged and confident peers.

As I think back on that 11th-grade English class, I’m not exaggerating to say that I have only positive memories of the lessons in Ms. Russing’s classroom. If anything bad happened, I don’t remember it.

That isn’t the case, however, with my other high school English classes, where the two teachers—one an abusive man, the other an overly strict woman—managed their classrooms through fear. They started out tough to get us kids under control, and they rarely let up.

One thing I did learn in those bad classes, though, was what not to do as an English teacher myself later on.